The Most Important Scene in Terminator History Is a Deleted One

In the Terminator franchise, history is always being rewritten — both onscreen and off. Within the movies, the villains from the future are trying to kill their most despised enemies before they can become a threat, and the heroes are trying to prevent future historical events from coming to pass. Behind the scenes, the makers of these films have repeatedly revised what is and is not part of official continuity. Terminator Genisys sent additional robots back into the events of Terminator 1 and 2, creating an alternate timeline, and the new Terminator: Dark Fate pretends the third, fourth, and fifth movies never took place and imagines a completely different version of its world. The characters in The Terminator like to say that there’s no fate but what we make, and boy is that ever true within this franchise. Never has fate been more mutable than it is in The Terminator.

In fact, one of the single most important scenes in the history of The Terminator franchise, at least in terms of the continuing health of the series and enabling all of these sequels, is one that was deleted. If it had been left intact, the Terminator timeline could have looked a lot different; for one thing Terminator: Dark Fate could not exist in the form that is arriving in theaters now. Removing it, mostly for the sake of expediency at the time, averted all kinds of future disasters, like an act of rewriting history almost immediately after it happened.

The key scene is from Terminator 2: Judgment Day, during a lull in the action near the midpoint. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s reprogrammed T-800 has just rescued Edward Furlong’s John Connor — a young boy who will supposedly lead the human resistance in their future war against machines like the Terminator — and his mother, Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) from the liquid metal grasp of the T-1000 Terminator (Robert Patrick), and now they’ve hunkered down in an abandoned gas station to lick their wounds.

Removing slugs from the Terminator’s torso prompts John and Sarah to ask the machine questions about its existence. Do the bullets hurt? (They register as injuries, and that data “could be called pain.”) Will the wounds heal? (With time, yes.) Can the Terminator learn? The T-800 replies that its CPU is a neural-net processor; a “learning computer.”

This is where the timelines branch.

In the version that played in theaters and on early home video releases — and therefore is considered part of the official continuity of the Terminator franchise — director James Cameron cuts away from Schwarzenegger as he speaks, and dubs in the line “The more contact I have with humans, the more I learn.” In the original script, though, this scene initially went on for several more minutes, and the Terminator gave a very different answer to this question.

Yes, Terminators can learn, but only if the chips in their brain are manually switched from read-only to write access. With the T-800’s help, John and Sarah open up the Terminator’s skull, remove the CPU, and flick the switch. Sarah, who distrusts the Terminator because one killed the love of her life and tried to murder her, wants to destroy the chip completely. John convinces her to at least try to teach it to be more human.

Here is that extended version of this scene:

On the director’s commentary track for T2, Cameron says there was a very simple reason he removed this sequence: Time. “You’ve got to remember,” he explains, “we had a movie that was running about two hours and 40 minutes. There was just no way that we felt we could play it. At that time, it was a slightly different world. Even big epic films were not very long. When I say not very long, two hours and 15 minutes, two hours and 20 minutes. Our goal was two-twenty, and that’s what we hit. But things had to come out.”

Interestingly, Cameron says this roughly four-minute chunk is the only deleted scene that he “misses” when he watches the theatrical cut of the film, primarily because it was a “pivotal moment” for the John Connor character; it shows his first steps towards becoming the leader that his mother claims he will grow up to be. But while Cameron also notes that it’s “not an Arnold scene at all,” removing this element had decades-long ramifications for the Terminator character.

Without this scene (which is included in the Terminator 2 Special Edition), it became canon that the longer Terminator robots remain active, the more they learn, and the more human they can become. In T2, we watch the T-800 learn to look for keys before it tries to hotwire a car and add slang like “Hasta la vista, baby,” to its vocabulary. In the final scene, it quips “I need a vacation.” In a matter of days, this robot has gone from a stone-faced killer to a large piece of metal that makes actual jokes.

Without spoiling the specifics, the Schwarzenegger role in Terminator: Dark Fate would not be possible if Cameron had decided to leave the switch scene in T2 and the concept of flipping the robots from read only to write in the movie. (He could be in the movie in some other way, but the specific character he is playing only makes sense without the chip scene.) Cameron’s originally concept would have lead to a far more robotic Terminator. The notion that the T-800 can only approximate naturalistic behavior after people slice off his hair, reach inside his robot brain, and tap a button distances the audience from that character foregrounds all of its eventual progress as an expression of an inhuman machine. He’s not becoming more human; he’s just faking it better. Allowing the Terminator’s lessons with John to simply be a part of his natural state makes him seem like more of a person. He’s growing the same way anyone else would in that situation. His actions have direct consequences on his emotional well-being the way they would a human.

James Cameron might have removed the chip scene purely to shrink the running time, but doing so greatly enhanced the emotional impact of the Terminator’s arc as well. It changes Terminator 2 from the story of a machine programmed to be good to one about a machine comprehending the nature of goodness on its own. On a philosophical level, that also opens up a lot more interesting areas to consider regarding the sentient nature of these machines. If they can learn and grow and crack jokes and maybe even feel sadness — and they can do all of that without outside influence from a programmer or a person flicking a switch — how different from us are they really?

Note: As Amazon Associates, we earn on qualifying purchases.

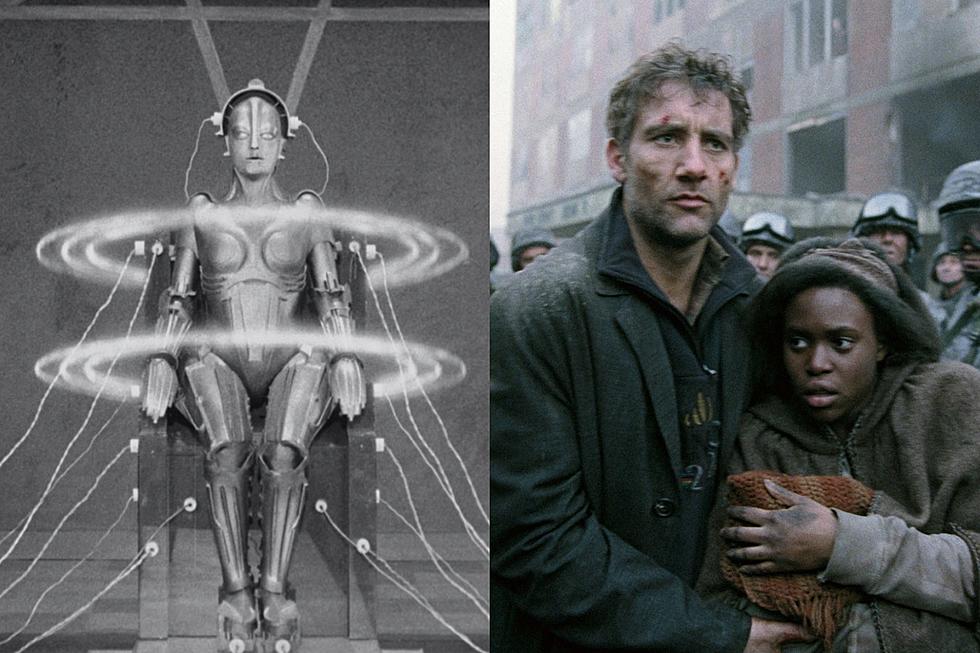

Gallery — The Best Sci-Fi Movie Posters:

More From WDBQ-FM